By John Grove

In January, Dr. Grove published an article in Polity examining the role of the public will in The Federalist Papers. Reflections takes its name from Alexander Hamilton’s iconic statement about the possibility of government directed by “reflection and choice.” Yet The Federalist is not exactly positive about democracy. Throughout, it indicates that democracy is prone to factionalism: the division of society into groups devoted to pursuing their own narrow interests rather than those of the whole. Yet, The Federalist also indicates that it is important for any government to be “popular,” deriving its authority from the people. In understanding exactly what The Federalist says about democracy, Dr. Grove argues that it is important to remember that it was written by different authors, and that those authors may have had slightly different viewpoints on what exactly is problematic about democracy and how a good government can address these faults:

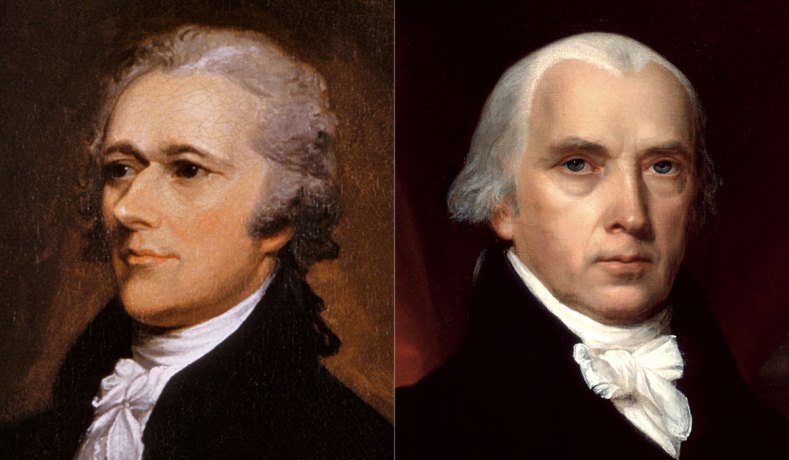

The two primary authors of The Federalist, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison offered differing and conflicting accounts of the precise cause of factionalism and the manner in which the public will could safely be accommodated within the constitutional system. Alexander Hamilton believed that demagogic leadership was responsible for stirring up the otherwise politically apathetic citizenry into factional groups. The common citizen, he believed, was naturally uninterested in politics, preferring to focus on his own private life. This also meant, however, that the common citizens is relatively uninformed about political life and therefore susceptible to clever politicians know just how to “flatter [the people’s] prejudices and betray their interests.”[1] He even calls these petty politicians “parasites and sycophants” who are willing to sacrifice the permanent good of society in order to win a position of power for themselves. As such, Hamilton believed the key to a successful political system was constructing it in such a way that allowed better leaders, those who cared not about gaining temporary popularity, but about achieving great things for their country, to occupy positions of authority. He believed the presidency was the key to this: Public opinion could be unified around the person and character of the president, preventing faction so long as that office was held by a person of great vision and high ambition. As such, Hamilton put his faith in the Electoral College, the unlimited number of terms available to a president, and the robust powers of the office to attract the highest quality of leader.

James Madison, however, saw factionalism arising naturally, without any impetus from poor leaders. “The latent causes of faction” were “sown in the nature of man,” he wrote.[2] This mean that, whatever quality of leadership may exist, factions will always arise in popular governments. Therefore, they must be accommodated and moderated in the best way possible. Madison relied not on the president to do this, but a carefully crafted and limited legislature capable of refining the public will. Representatives would naturally reflect some of the biases of their constituents, but they would be placed in an environment which allowed for and encouraged healthy dialogue and compromise on the common good. Their terms would be just the appropriate length to provide a degree of independence from the factional will of the people, while still being ultimately answerable to it; the size of the legislature would be too large for casual intrigue and corruption, but too small to devolve into a mob; and the constitutional limitations on Congress’ power would mean representatives would be discussing broad, national issues and avoiding local concerns most likely to pit factions against one another.

Understanding The Federalist in this way allows it to illuminate questions which continue to press on us today: To what extent are the divisions in American politics caused by naturally arising identity and interest groups, and to what extent are they stirred up by the rhetoric of provocative leaders? Do we find the solution in unifying leaders, or in deliberation and dialogue? As is often the case, a careful reading of this great work can continue to offer wisdom and a framework within which to consider these political puzzles.

Dr. Grove’s full paper can be found here for those with access.

[1] The Federalist, No. 71

[2] The Federalist, No. 10